Group Housing Gilts & Sows: What’s the Story? >>How Did We Get Here & Where Are We Headed?

By: Stephanie Cottee, PhD., Animal Welfare Manager, Probiotech International

Changing Customer Requirements

The push towards alternative housing systems and improved quality of life for pigs is due to a myriad of factors. No doubt, animal rights activism has strengthened its platform by leveraging social media and strategically incorporating themselves into key conversations and networks within the animal protein supply chain. This has greatly enabled animal activist agendas to gain greater public visibility. In addition, now more than ever, consumers are curious about where their food comes from and how it’s produced. They not only expect their food to be affordable, safe and nutritious, but also ethically and sustainably sourced.

Studies have shown that consumers take these aspects into consideration in their purchasing decisions. With respect to pork production specifically, many concerns have been about production practices related to pig welfare (Cummins et al. 2016). McKendree et al. (2014) found that 14% of U.S. consumers had reduced their pork consumption because of pig welfare concerns. Much of this concern is related to confinement housing and the perception of a severe lack of space, restricting animal movement and expression of natural behaviours. Consumers expect livestock animals to be provided a good quality of life and reject anything that appears unnatural or subjects animals to pain, fear or distress.

Product labels like ‘vegan’, ‘organic’, ‘welfare-friendly’, ‘cage/crate-free’, and ‘pasture-raised’, used to be hard-to-find, specialty items available only in high-end food marts. Today, these types of products have diversified and proliferated and these labels can be found even in discount-grocery stores; they are no longer a niche market or temporary trend, but rather mainstream.

What’s the Concerning Issue?

The Challenges of Group Housing

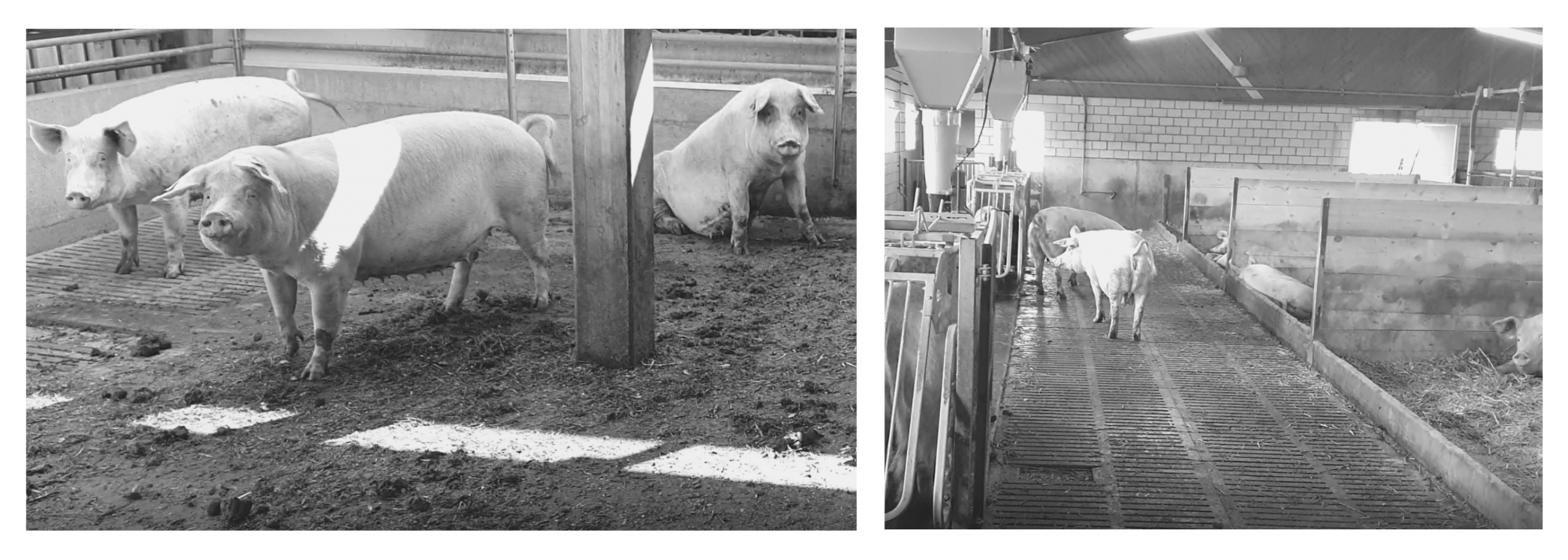

Under natural conditions, pigs live in small established groups, breed, gestate and give birth, all without confinement. Under modern large commercial scale production, the process of reproduction is a highly controlled science. Key goals include successful breeding/pregnancies/farrowing and the production of large litters of healthy piglets. In order to meet these goals, several things must be carefully controlled, including nutrition and pig stress. In a group of pregnant sows allowed to co-mingle, it is difficult to manage the ration of food that each animal receives as inevitably some pigs will eat more than their share, resulting in some animals to overeat while leaving others underfed. In addition, when pigs are mixed into new social groups, unfamiliar animals will physically fight in order to establish their position within the new hierarchy; this causes stress and injuries to the sows. Fortunately, solutions to these problems do exist (described in Table 1).

The Challenges of Gestation Stalls

In order to circumvent the aforementioned problems with group housing, impregnated gilts/sows can be housed in individual gestation stalls, which physically isolates them from other animals for the duration of their pregnancy. This allows for greater individual care and management, precision feeding and prohibits any fighting between animals, all of which promote a higher likelihood of a safe and successful pregnancy.

However, although there are many health benefits to be had by social separation, there remain features of the gestation stall that decrease some aspects of pig welfare – namely restricted space and movement. Sows are usually introduced into gestation stalls at the beginning of their pregnancy, but continue to get bigger and heavier as their pregnancy progresses. One study showed that the majority of sows cannot fit in a conventional gestation stall without their body parts protruding outside of, or being compressed against the stall sides (McGlone et al. 2004) and over the past few decades, stall sizes have essentially remained the same.

Public Concern

Given the welfare problems associated with extreme confinement, animal welfare advocates argue that the crux of the issue isn’t about isolation per se, as it is about the small cage size and severe restriction of movement and the inability to express natural pig behaviours – the lack of which can cause sow frustration, psychological distress and the development of stereotypies (Broom et al. 1995; Vieuille-Thomas et al. 1995).

How do We Address the Concerning Issue?

Sows can be kept in different types of housing during pregnancy. Generally, the main types include gestation stalls, group pens, and free-range systems, and there exists within each type, a significant amount of variation in design. Also note that in addition to the different systems and their variations, welfare outcomes are influenced by many other factors, such as husbandry, management, genetics, the sows’ previous experience, feeding practices, flooring, bedding types and temperature (AVMA, 2015).

Gestations Stalls

As aforementioned, the advantages of gestation stalls include easy individual sow identification, individualized diets and prevents sows from physically injuring each other from fighting. Disadvantages of the average 7 X 3 ft stall includes restricted movement to only sitting and standing, higher incidence of stall-induced injuries such as pressure sores and abrasions (Gjein and Larssen, 1995; Boyle et al. 2002; Karlen et al. 2007) and the development of stereotypic behaviours (indicative of negative mental affect like frustration and boredom) like chronic bar biting, chewing and licking (Broom et al. 1995; Chapinal et al. 2010; Zhou et al. 2014).

Group Housing

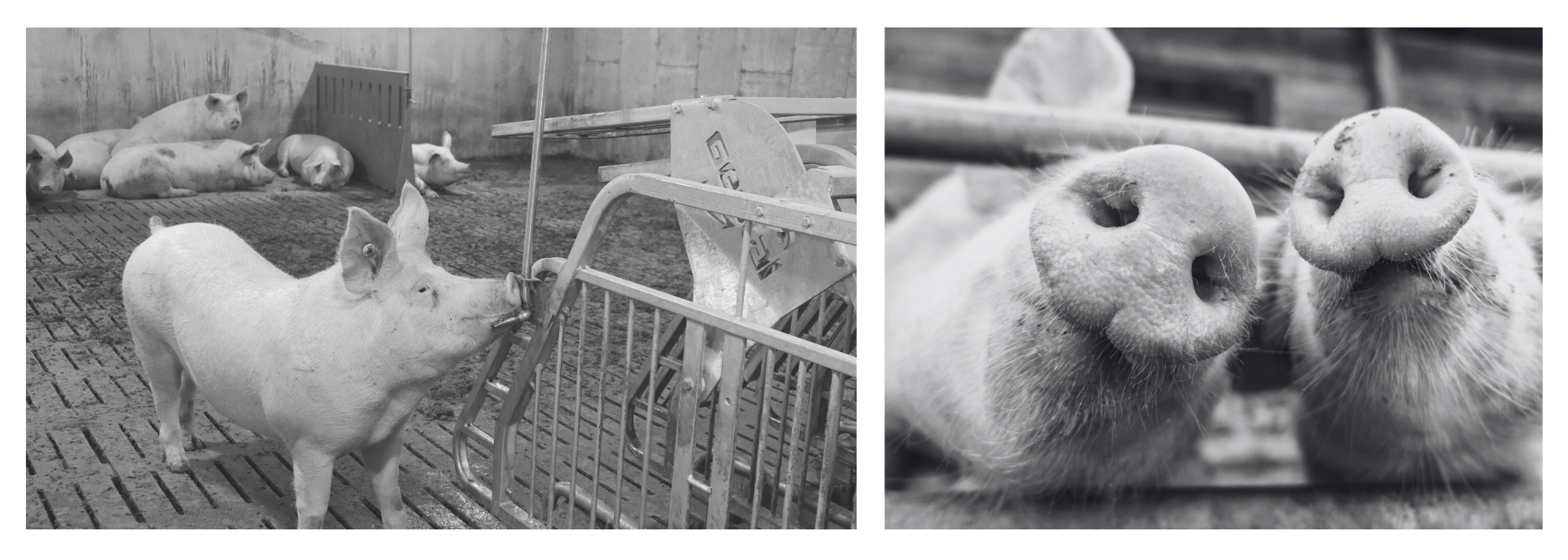

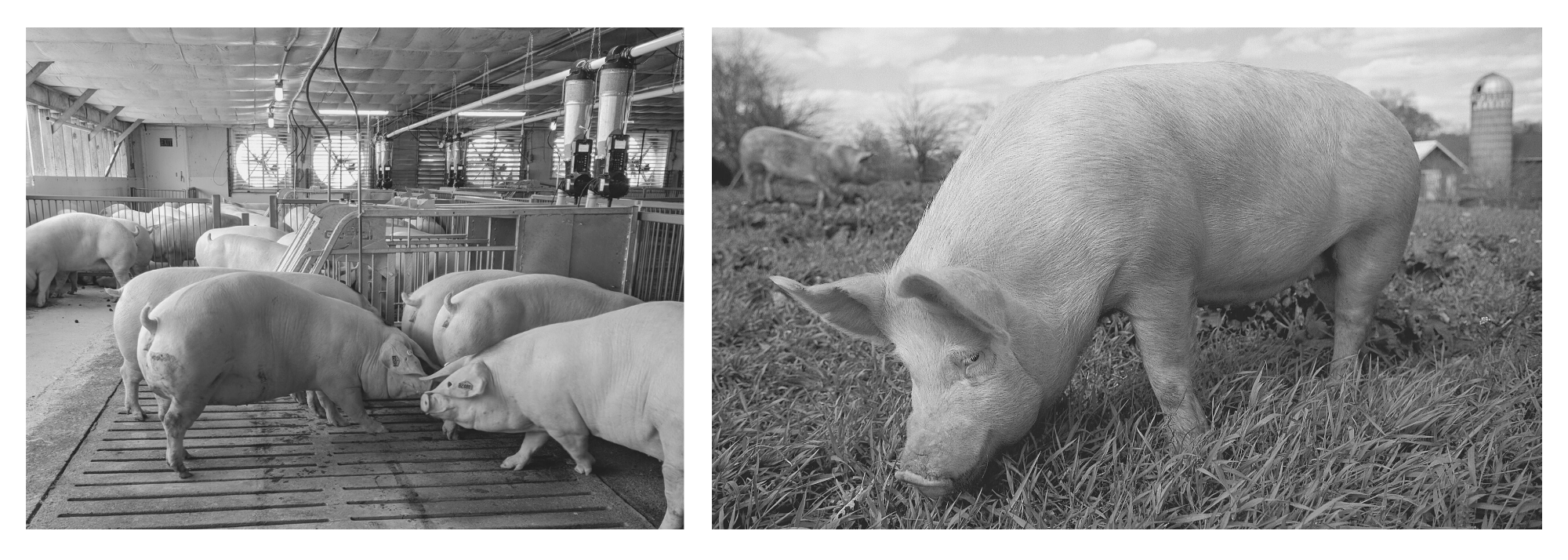

Group housing therefore addresses the concern of confinement and isolation. In indoor group pens, pigs are kept in groups of various sizes from a few to a couple of hundred animals. In North America the most common is the indoor system with slatted floors, though alternative group systems like hoop barns (ie. Tent-like, naturally ventilated, straw-bedded systems) may also exist in geographies with suitable climates.

In social group settings, gilts and sows have the opportunity to socially interact physically with each other and also have freedom of movement within their enclosure. The main disadvantage of permitting animals to have full body contact with each other however, is the psychological and physical damage to the pigs due to aggression and fighting. Fighting could be caused by competition for resources or by changes in social structure (either by adding and/or removing animals to the group) (McGlone and Salak-Johnson, 2008). However, if managed correctly, group housing can be as productive and effective as stall housing.

Free-range Systems

In free-range systems, the behavioural opportunities are even greater. Access to outdoor range can permit foraging/rooting, wallowing, and manipulation/consumption of natural vegetation and insects etc. The addition of large outdoor ranges may also reduce aggression as it gives extra space and opportunities for subordinate pigs to avoid aggressors. Disadvantages include more risk of disease (bacteria and viruses from wild vectors) and parasites as well as exposure to uncontrollable outdoor climatic conditions.

How do we mitigate the disadvantages of group housing?

Producers have legitimate concerns about the cost of new barn infrastructure and also how to manage an alternative group housing system, in particular, pig aggression. Successful sow/gilt fertility and pregnancy ultimately depend on a precise series of hormonal events. Stress can easily disrupt any part of this process of events, resulting in reproductive failure.

A major stressor is pig fighting and aggression. Fighting happens most intensely in the immediate period upon social mixing as individuals establish and/or re-establish their group hierarchy. Fortunately, the aggression and fighting can be mitigated with the implementation of certain management practices as suggested by Knox and Estienne (2013) (Table 1):

In addition, new research is showing that the addition of certain supplements to the drinking water or feed can reduce aggression and fighting by keeping animals calmer and relaxed. Brown et al. (2017) found that pigs supplemented with a phytogenic neurosensory product (Phytozen® Liquid, Probiotech International) 3 days prior and post-mixing, showed significantly decreased duration of behavioural threats during initial mixing. There was also a significant decrease in moderate and severe skin wound lesions compared to un-supplemented pigs. In a different study (Ory, 2016), the same product significantly decreased the amount of cannibalism by more than half. Therefore, supplementation with certain products is showing good promise as an innovative tool in the management of pig aggression.

Legislative Mandating of Welfare Requirements – Examples Around the World

The topic of gestation and even farrowing stalls has become increasingly controversial. In response to the public unease with animal confinement systems, many parts of the world have mandated a change in how pigs are housed.

North America

In United States, 14 states have banned ‘extreme confinement’ and a number of others are currently following suit (ASPCA, 2021). For example, California’s “Proposition 12”, a state ballot initiative, is mandating that all breeding pigs be given at least 24 square feet of usable living space and to ban in-state sales of raw pork products not produced under these requirements by January, 2022. Although California is only one state, it alone accounts for approximately 15% of the nation’s pork market (National Pork Producer’s Council, 2021).

In Canada, its pork industry has pledged to phase-out gestation crates, aiming to be crate-free by 2024. But as the deadline quickly approaches, stakeholders are now asking for an extension of another 5 years, hoping to move the deadline to 2029.

Europe

The European Parliament has called for the end of farming with the use of all cages within the next 6 years. The parliament members voted on a cage ban in animal agriculture by 2027. In fact, loose farrowing pens are increasingly promoted and implemented. For example, New Zealand’s High Court ruled the use of farrowing crates to be unlawful. In response, the government is mandating a cage phase-out over 5 years aiming for a deadline of 2025.

Asia

Not surprisingly, changing attitudes are not exclusive to ‘Western’ culture. China is the world’s largest producer and consumer or pork; although they have no pig welfare legislation, change is being driven by customer demand. According to a survey commissioned by World Animal Protection (WAP, 2016), over 83% of Chinese consumers want to see production systems that give pigs the freedom to move (ie. not confining pigs to stalls). Indeed, decreasing stall usage has already begun, with group sow housing being implemented in a large and growing number of Chinese pork producing companies (CIWF, 2021).

Industry Push-Back

However, not everyone is supportive of these changes. For example, In the United States, the North American Meat Institute (NAMI), the largest trade association representing U.S. processors and packers of livestock and poultry, tried blocking Proposition 12 as they believe the proposed changes will cost producers and consumers too much money and is not economically viable; they also question the constitutionality of Proposition 12. NAMI attempted to challenge the ruling, but the US Supreme Court denied the petition from the NAMI to hear its case regarding the constitutionality of Proposition 12; And so, the proposed changes are still moving forward. This sentiment is not unique to the US, as the industry in general is fragmented with regards to their support for a complete phase-out of cages; while some producers support it, others do not and some other would rather see choice given to producers rather than it being mandated.

Additional Drivers of Change – Examples from the Food Sector

Currently, the poultry welfare movement is going strong; producers are challenged with moving laying hens out of cages and into cage-free systems or being pushed to consider replacing their fast-growing broiler breeds with slower growing strains in efforts to alleviate the cardiac and musculoskeletal concerns of their heavy, fast-growing counterparts. Hundreds of multinational food business stakeholders from producers to restaurant chains to grocers/retailers to food service companies have made pledges to source their poultry products from suppliers who meet these new bird welfare requirements.

The pork industry too, has been following suit with similar asks. Many of the same food companies who have announced their public commitments to improving bird welfare, have likewise pledged to do the same for pig welfare; the major promise they have committed to, is the elimination of gestation stalls (or ‘gestation crates’) from their supply chains.

The Changing Face of Food Animal Welfare

In summary, the landscape of food animal welfare continues to evolve. As the global human population continues to dramatically increase, it is being met with an increasing demand for animal protein. Therefore, it is unlikely that conventional production systems will ever go extinct. Rather, the high demand for protein makes more room for producers to diversify and meet the consumer and customers’ desire for different purchase options that fit their various levels of food affordability and correspond to their personal values.

References

American Veterinary Medical Associated (AVMA) (2015). Welfare Implications of Gestion Sow Housing.

ASPCA (2021). Farm Animal Confinement Bans by State.

Boyle L.A., Leonard F.C, Lynch P.B. and Brophy P. (2002). Effect of gestation housing on behavior and skin lesion scores of sows in farrowing crates. Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 76:119–134.

Broom D.M., Mendl M.T., and Zanella A.J. (1995) A comparison of the welfare of sows in different housing conditions. Animal Science, 61:369-386.

Brown J., Beaulieu A. Denise, and Seddon M. Yolande (2017). Effects of a novel compound on aggressive behaviour in grow-finish pigs. Advances in Pork Production. Volume 28: Abstract #1

Chapina N., Ruiz de la Torre J.L., Cerisuelo A., Gasa J., Baucells M.D., Coma J., Vidal A., Manteca X. (2010). Evaluation of welfare and productivity in pregnant sows kept in stalls or in 2 different group housing systems. Journal of Veterinary Behavior: Clinical Applications and Research 5: 82-93.

Compassion in World Farming (2021). Good pig Production Award.

Cummins A.M., Widmar N.J.O., Croney C. and Fulton J.R. (2016). Understanding Consumer Pork

Attribute Preferences. Theoretical Economics Letters, 6: 166-177.

Gjein H. and Larssen R.B. (1995). Housing of pregnant sows in loose and confined systems–a field study 1. Vulva and body lesions, culling reasons and production results. Acta Veterinaria Scandinavica, 36:185-200.

Karlen G.A.M., Hemsworth P.H., Gonyou H.W., Fabrega E., Strom A.D., and Smits R.J. (2007). The welfare of gestating sows in conventional stalls and large groups on deep litter. Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 105:87-101.

Knox RV and Estienne MJ. (2013). Group Housing Systems: Forming Gilt and Sow Groups. National Pork Board. 800-456-7675.

McGlone J.J. and Salak-Johnson J. (2008). Changing from sow gestation crates to pens: Problem or opportunity? In Proceedings: Manitoba Swine Seminar, Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada. pp.47-53.

McKendree M.G.S., Croney C.C. and Widmar N.J.O. (2014) Effects of Demographic Factors and Information Sources on United States Consumer Perception of Animal Welfare. Journal of Animal Science, 92: 3161-3173.

National Pork Producers Council (2021). California Proposition 12.

Ory N. (2016) – L’apaisement des porcs : leur bien-être et celui des éleveurs. Cooperl Arc Atlantique Magazine – Octobre 2016, p 14-15.

Vieuille-Thomas C., Le Pape G. and Signoret J.P. (1995). Stereotypies in pregnant sow: indications of influence of the housing system on the patterns expressed by the animals. Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 44:19-27.

World Animal Protection (2016). Chinese consumers support better welfare for pigs.

Zhou Q., Sun Q., Wang G., Zhou B., Lu M., Marchant-Forde J.N., Yang X. and Zhoa R. (2014) Group housing during gestation affects the behaviour of sows and the physiological indices of offspring at weaning. Animal, 8; 1162-1169.