Group Housing for Sows:

A Guide to Sustainable Pig Farming

Dr. Jennifer Brown’s presentation at the GESTAL Swine Summit 2022 focused on the complex relationship between group housing and sow health, productivity, and welfare.

Group housing systems for sows, increasingly favored to meet consumer and retailer demand for improved animal welfare in swine production, bring both opportunities and challenges for the pork industry.

The Challenges of Group Housing

Alongside the transition to group housing in gestation, certain crucial issues may be exemplified, including increased mortality and culling rates. Key contributors include: heightened sow aggression and competition for resources, lameness issues, and reproductive challenges. Data highlights that lameness alone accounts for nearly 29% of sow removals, while 39% are classified under “unknown causes.” This calls for better postmortem procedures and farm data collection to identify and mitigate these issues.

One major issue stems from social behaviors. While taking sows out of stalls aligns with the principles of sow welfare, it inadvertently promotes the establishment of social hierarchies among sows, leading to aggression. Injuries, pregnancy losses, and unplanned culling are frequent outcomes. These challenges require ongoing research into sow behavioral management and best practices for group housing in pig farming to optimize productivity while prioritizing welfare.

Understanding Sow Welfare

Dr. Brown explored the concept of sow welfare through David Fraser’s framework, which includes:

- Functional State – Stresses metrics like productivity and health.

- Natural Living – Focuses on enabling normal behaviors, such as foraging and social interaction.

- Affective State – Considers emotional well-being, emphasizing whether animals are suffering or thriving.

When group housing systems are well-managed, herd productivity can easily be maintained or even improved from traditional practices. But key issues of the functional perspective such as high mortality rates and feed competition need targeted solutions to fully realize the welfare benefits. Consumers are increasingly demanding changes that could improve sow welfare, but success depends on learning and implementing these practices correctly.

Benefits of Group Housing for Sow Welfare

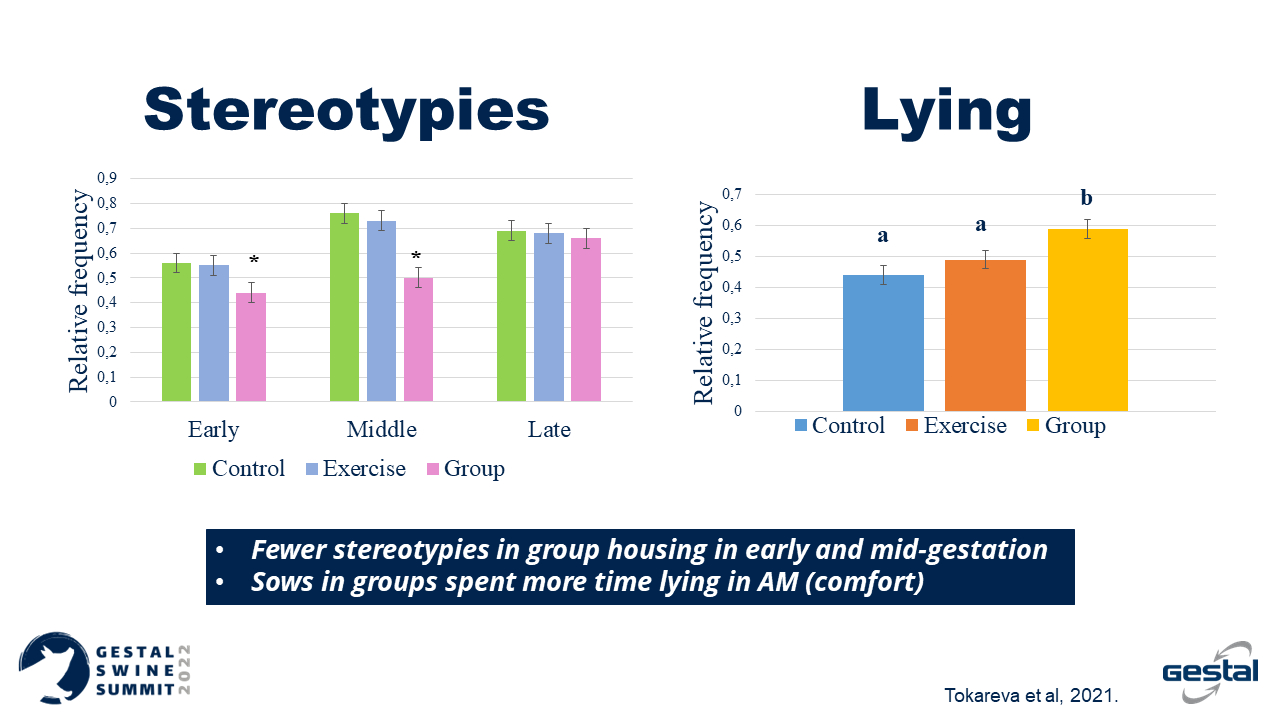

A recent study by Maria Tokareva at Prairie Swine Center on 180 sows explored the effects of housing treatments on sows. Three treatments were applied to assess sow welfare: 1) control – sows remained in stalls all the time; 2) sows housed in groups; and 3) sows kept in stalls while exercised weekly for 10 minutes.

Maria’s research showed significant differences:

- Fewer stereotypies in group housing in early and mid-gestation.

- Sows in groups spent more time lying in the AM (comfort).

- Reduction of the number of stillborn piglets, both in the exercise and in the group housing situations, an effect observed also in other studies.

Such benefits underscore the potential of transitioning toward sustainable pig farming, in line with Canadian farming codes mandating group systems by 2029.

Addressing Aggression in Group-Housed Sows

Mixing Aggression

Mixing aggression occurs when sows are grouped together to establish a social hierarchy, typically lasting 2 to 10 days. Aggressive behaviors include head knocks, pressing or biting, often targeted at subordinates.

Key Strategy: Adequate space within pens allows subordinates to retreat, reducing aggression impacts.

Ongoing Competitive Aggression

This form of aggression persists throughout gestation, particularly in systems with limited feeding areas or resting spaces. It is less intense than initial mixing aggression, often displayed as avoidance behavior rather than overt physical aggression.

Factors Influencing Aggression and Key Solutions

While stall housing offers simplicity, managing group-housed gestation poses complex challenges. Multiple factors intersect, and there is no single solution yet to effectively minimize aggression while optimizing welfare and productivity. Research in this area continues to evolve to address these questions.

Several variables affect aggression levels among sows, including:

- Early vs. late mixing of groups.

- Dynamic vs. static grouping systems.

- Space allowance and pen design.

- Feeding systems, diet composition, and satiety improvements.

1. Mixing Timing:

Studies indicate that aggressive behaviors, such as increased skin lesions and lameness, tend to occur with early mixing, particularly before implantation (during the first week after insemination). Research by Stevens et al. (2015) and Knox et al. (2014) shows that early mixing (days 2–9 post-insemination) may lead to higher aggression and lower conception and farrowing rates compared to mixing later (5–6 weeks post-insemination or days 35–46). However, the practical application of early mixing can save barn space and reduce the number of breeding stalls required, making it an efficient use of resources during transitions.

Researchers and swine producers employ various strategies to reduce aggression during sow mixing, aiming to enhance their welfare and adjust to social dynamics. Promising methods include pre-mixing pens for dynamic groups and dedicated mixing pens with better flooring and space allowances for static groups, showing positive results. Other approaches like introducing a boar, masking scents to improve acceptance, or mixing sows late in the day have had mixed success, often delaying aggression rather than eliminating it. Ensuring sows are well-fed is another essential factor in mitigating aggression.

Pre-mixing pens prove particularly effective when sows interact post-weaning during the breeding phase, leading to lower aggression levels, more inactivity, and a calmer environment compared to unmixed sows. Research on the timing of mixing sows after insemination provides mixed conclusions, though it highlights important management considerations.

-

- Early mixing (2-9 days after insemination) often leads to higher aggression and reduced conception rates.

- Late mixing (35-46 days post-insemination) allows for fewer injuries, though results can vary.

Advisory:

- Success depends less on timing and more on execution. Effective strategies, whether static or dynamic group systems, focus on space optimization and flexibility while minimizing stress through proper implementation.

- Dynamic systems, though gaining popularity due to flexibility and efficient pen use, demand greater attention to repeated grouping concerns and overall management practices.

2. Dynamic vs. Static Groups

Lameness and skin injuries in sows housed in dynamic and static groups have been studied extensively, with varying results depending on multiple factors. Studies, such as those by Li (2017) and Anil (2006), have found that dynamic groups show higher levels of chronic skin injuries and lameness compared to static groups throughout gestation. However, significant differences were not observed during mixing periods. Cortisol levels and performance also remained unaffected, indicating only a moderate impact from grouping styles.

The propensity for injuries in dynamic systems may be influenced by floor type and competition among sows, as noted by researchers. Conversely, other studies, like Payam’s, found no difference in lameness prevalence between static and dynamic grouping systems, though group housing overall presented higher lameness levels, regardless of system style. The outcomes largely depend on external factors such as environment and management practices, underlining the complexity of housing decisions in sow welfare.

3. Space Allowance and Pen Design

Space allowance also remains a critical yet unresolved issue. While ranges from 15 to over 32 square feet were explored, researchers suggest the optimal allowance likely falls between 19 and 26 square feet, though further investigation is necessary. Feeding systems and their interaction with space allowances also require additional evaluation to determine best practices for welfare and productivity in varying herd environments.

Aggression and social dynamics among sows are heavily influenced by pen design, parity grouping, and satiety. Research by Barnett et al. (1993) shows that rectangular pens with longer distances can reduce aggression by giving sows space to escape conflicts. Grouping sows by parity, especially segregating gilts, has proven benefits. Mixed-parity groups establish a rigid social hierarchy, often leaving gilts at a disadvantage, resulting in more skin lesions and fights. As shown by another study by Li et al.(2017) , uniform groups, however, experience fewer injuries and better outcomes, such as higher farrowing rates and improved back fat levels in parity-one sows.

- A study by Hemsworth et al. (2013) on the effect of increasing space allowance showed increased farrowing rate, reduced feeding aggression and reduced cortisol levels.

- A study by Mack et al. (2014) on increased space allowance showed no difference, positive or negative, on productivity or time out of stall in a free access system.

- A study by Pluym et al. (2017) on the effect of increasing space allowance showed a reduction in lameness.

- A study by Li et al. (2017) showed an increase in lameness following an increase in space allowance.

- A study by Salak-Johnson et al (2007) on increased space allowance showed an increase in lameness.

Insight: The impact of pen designs on sow welfare highlights the need for proper configurations to promote harmony and reduce aggressive incidents, not just focus on space allowance per se. Further investigation on the subject is necessary.

4. Feeding Systems

Satiety plays a critical role in managing aggression. Sows, often restricted to 50% of their desired feed intake, experience prolonged hunger, leading to heightened aggression and stress. Addressing this with high-fiber diets, including soluble and insoluble fibers, shows promise in improving gut health, satiety levels, and overall welfare.

The European Union’s decision to mandate fiber levels in animal feed is a step in the right direction, highlighting the importance of understanding the impact of different fiber sources. Certain European farms are tackling the challenge by providing fiber ad lib outside of electronic sow feeding (ESF) systems to balance increased feeding times. However, this solution requires adjustments, such as bigger hoppers and longer consumption periods, which may result in increased manure volumes and potential greenhouse gas emissions.

Ensuring the sustainability and biosecurity of feed is vital, especially in regions like Western Canada and North America. Sourcing and processing suitable materials that are biosecure and compatible with on-farm systems is key. While challenges around increased feed quantities and environmental effects exist, ongoing innovations in feed delivery systems and fiber management can help optimize animal health and productivity.

Hunger-induced aggression underscores the importance of better feeding systems for sows, such as automated precision feeding systems. High-fiber diets can increase satiety, alleviate stress, and improve behavior.

Additional Solutions for Improving Sow Welfare

Additional solutions to enhance sow welfare include tailored nutrition plans for gilt development, early socialization practices for piglets, and selective breeding focused on improvement of structural confirmation. Management practices such as floor scraping, high-risk area drying powders, and worker-focused barn designs were also highlighted as critical for maintaining cleanliness and improving air quality.

Innovative technologies, like automated feeding systems and AI-powered lameness detection tools, hold significant promises for identifying health issues early and supporting safer heat detection.

Understanding Sow Lameness and Its Measurement

Challenges like lameness remain a significant issue in sow welfare, often leading to removals or culling. Unlike aggression, lameness is easier to observe and measure. Research in this area often references advancements in dairy cattle management, though swine-specific solutions are still in development.

Sow lameness significantly impacts weight-bearing and mobility, primarily due to the animal’s anatomy and modern breeding practices. The front legs of sows are naturally robust, bearing much of their weight, similar to other farm animals like horses. However, by increasing litter sizes and frame size, their hind limbs become more prone to issues. Challenges often surface during gestation, where sows struggle to rise or move without assistance.

Methods for Assessing Lameness

1. Visual Assessments:

- Commonly used on farms due to simplicity.

- Includes subjective scoring systems, ranging from 3 to 9 categories, such as the Zinpro scale (0-3). Scores range from fluid movement (0) to reluctance or inability to bear weight (3).

- While suitable for on-site evaluations, variability between observers affects accuracy.

2. Scientific and Automated Tools:

- Researchers aim for quantitative methods to improve precision. Innovations include kinematics, pressure mats, and accelerometers to analyze gait and posture.

- Technologies like force plates, latency-to-lie monitoring, and weight distribution analysis provide deeper insights. However, these systems, such as those integrated into electronic sow feeders, are often costly.

Effective Methods for Reducing Lameness in Group-Housed Sows

Bedded pens

Bedded pens have emerged as a proven method to reduce lameness, improve leg health, lessen aggression, and increase satiety among pigs, suggesting possible adoption of these systems in the future. These advancements reflect a growing focus on ensuring the welfare and health of pigs in farming operations.

Flooring

Flooring plays a critical role in leg health, but more research is needed to explore aspects like slat and gap width, as well as surface abrasiveness versus slipperiness. Recent studies in Canada, by Devillers et al. (2020), have explored how slat and gap widths in flooring impact sow movement and comfort. Findings show that smaller gap widths and wider slats are more effective, reducing hoof lesions and contributing to normal lying behavior without affecting reproductive performance or manure management. The EU recommendation of 20 millimeters seems to be better than higher gap widths.

Tackling Lameness in Pigs

Lameness remains a significant welfare concern, impacting weight-bearing, mobility, and often leading to removals. Solutions like bedded pens and carefully engineered flooring designs have shown promise in reducing lameness, while innovative tools such as kinematics and force plates provide deeper insights into managing the issue.

Researchers like Devillers have demonstrated how modifications in flooring, such as narrower gaps and wider slats, positively affect preventing injuries in group-housed pigs. These advancements align with efforts to reduce the impact of lameness in pigs in cost-effective, welfare-driven ways.

Innovative Management Techniques for Sustainable Pig Farming Practices

Leveraging Technology:

Deploying AI-powered lameness detection tools and automated feeders supports health monitoring and stress reduction, aligning with best practices for group housing in pig farming.

Sustainable Practices:

Sourcing biosecure, high-quality feed and leveraging real-time data systems reflect the growing push toward sustainable pig farming.

Farmers transitioning to group housing for sows must also mitigate environmental challenges, such as the increased manure volume posed by fiber-rich diets. The integration of eco-friendly systems is critical in addressing these concerns effectively.

The Path Forward for Group Housing Success

While implementing group housing systems may present challenges with its many different aspects intersecting, when well managed, the benefits to sow welfare and productivity can outweigh the downfalls. Advanced technologies, such as automated precision feeding systems, play a pivotal role in overcoming common feeding obstacles associated with group housing —ensuring optimal feed distribution and reducing competition.

Achieving sustainable, welfare-driven pig farming requires leveraging these technological advancements alongside real-time data, barn design innovations, and meticulous record-keeping for benchmarking. As explained by David Cadogan during a conference at the GESTAL Swine Summit 2022, by learning from global examples such as Australia’s rapid transition challenges, producers can avoid common pitfalls and establish best practices that support long-term success.

The transition to group housing isn’t just about meeting farming codes—it’s an opportunity to raise the bar for animal welfare, operational efficiency, and ethical farming practices. By adopting these systems, farmers take a meaningful step toward a more innovative and sustainable future. Now is the time to champion group housing and make smarter, more informed decisions for your farm’s success.

References

Anil, L., Anil, S. S., Deen, J., Baidoo, S. K., & Walker, R. D. (2006). Effect of group size and structure on the welfare and performance of pregnant sows in pens with electronic sow feeders. Canadian Journal of Veterinary Research, 70(2), 128–136.

Barnett, J. L., Cronin, G. M., McCallum, T. H., & Newman, E. A. (1993). Effects of pen size/shape and design on aggression when grouping unfamiliar adult pigs. Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 36(2-3), 111–122.

Brown, J. (2022). Aggression and lameness in group housing: Fine-tuning for success. Conference presentation at the GESTAL Swine Summit, Aggression and Lameness in Group Housing: Fine-Tuning for Success.

Cadogan, D. (n.d.). 12 years of stall free & electronic sow feeding: What we got right and terribly wrong,12 Years of Stall Free & Electronic Sow Feeding: What we Got Right and Terribly Wrong.

Devillers, N., Yan, X., Dick, K. J., Zhang, Q., & Connor, L. (2020). Determining an effective slat and gap width of flooring for group sow housing, considering both sow comfort and ease of manure management. Livestock Science, 242, 104275.

Fraser, D. (2008). Understanding animal welfare. Acta Veterinaria Scandinavica, 50(1), S1.

Hemsworth, P. H., Rice, M., Nash, J., Giri, K., Butler, K. L., Pitchford, W., & Morrison, R. (2013). Effects of group size and floor space allowance on grouped sows: Aggression, stress, skin injuries, and reproductive performance. Journal of Animal Science, 91(11), 4953–4964.

Knox, R., Salak-Johnson, J., Hopgood, M., Greiner, L., & Connor, J. (2014). Effect of day of mixing gestating sows on measures of reproductive performance and animal welfare. Journal of Animal Science, 92, 1698–1707.

Li, Y. Z., Wang, L. H., & Johnston, L. J. (2017). Effects of social rank on welfare and performance of gestating sows housed in two group sizes. Journal of Swine Health and Production, 25(6), 290–298.

Li, Y., Wang, L., Johnston, L. J., & Hilbrands, A. M. (2018). Effects of increased space allowance on lameness in group-housed sows. Translational Animal Science, 2(4), 409–418. https://doi.org/10.1093/tas/txy092

Mack, L. A., Ross, C., Crossman, S. M., & Johnson, A. K. (2014). Group space allowance has little effect on sow health, productivity, or welfare in a free-access stall system. PDF document.

Pluym, L. M., Van Nuffel, A., & Maes, D. (2017). Impact of group housing of pregnant sows on health. Preventive Veterinary Medicine, 139, 58–66.

Salak-Johnson, J. L., Niekamp, S. R., Rodriguez-Zas, S. L., Ellis, M., & Curtis, S. E. (2007). Space allowance for dry, pregnant sows in pens: Body condition, skin lesions, and performance. Journal of Animal Science, 85(7), 1758–1769.

Stevens, B., Karlen, G. M., Morrison, R., Gonyou, H. W., Butler, K. L., Kerswell, K. J., & Hemsworth, P. H. (2015). Effects of stage of gestation at mixing on aggression, injuries, and stress in sows. Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 165, 40–46.

Tokareva, M. (n.d.). Impact of group housing compared to traditional stall systems on sows: Comparing stalled housing, stalled housing with periodic exercise, and group housing [Study]. Western College of Veterinary Medicine, Saskatchewan.